A Brief History of Feminism in China

- Grace G.

- Apr 30

- 6 min read

Digital feminism is a relatively new phenomenon, emerging alongside the popularity of social media. However, feminism itself has long existed in China. However, the longstanding influences of belief systems like Confucianism that enforce strict gender roles on women have made it incredibly difficult for feminists to make any real improvement. The struggle between progress and tradition continues to this day. In terms of China as we know it today, the development of feminism can be divided into four phases: state feminism, market feminism, repoliticizing women's personal issues, and digital feminism (Hou 2020).

State Feminism

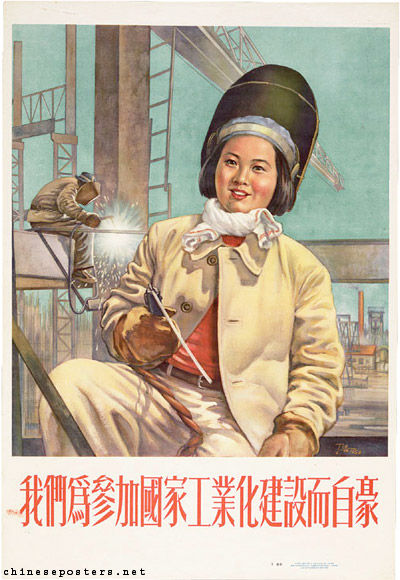

This phase incorporates the 1950s to the 1970s, which is essentially Mao's reign. The People's Republic of China was established in 1949, and it was led by Mao Zedong until 1976. Thus, the political sphere at this time was controlled by Mao and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Maoism theoretically advocated for gender equality, and it was even enforced in legislation. Mao is quoted saying "Women hold up half the sky". However, the implementation fell short. The focus was really on class struggles and economic development rather than gender equality. The All-China Women's Federation (ACWF) was created to represent women and push for gender equality. In some ways, it did, in conjunction with the state. In the public sphere, men and women were equal. The problem is that it ignored all problems in private life. Under Mao, every person's agency was taken away; they were tools of the state. Any expression of sexuality became taboo. Feminism and feminist discourse would ultimately be considered bourgeois, not characteristic of the common person Mao promoted. Instead, promoting gender equality was used to encourage and normalize women working in male-dominated fields because that would be useful for the state. This is best seen with the "Iron Girls", or "Iron Women", shown below.

Market Feminism

This phase incorporates the time period of China's market reform and opening up in the 1980s. This transition period was rough for everyone involved; it was a lot of change very quickly. In terms of feminism, market reform saw the state lower its control over the individual. The personal aspects of feminism became more prominent. State feminism politicized the women's body, so market feminism sought to depoliticize it. It also walked away from the push for women to do "men's work". Instead, it emphasized the gender difference. It encouraged women to choose what they do, including roles like a housewife, in order to regain the female consciousness, to rediscover their femininity. There are criticisms of market feminism, though. The biggest point of contention is that it conformed to the market, which sought to commodify women. The process of rediscovering femininity was heavily tied to consumption.

Repoliticizing Women's Personal Issues

The 1990s saw continued commodification of women. Feminist discussions had faded away, until the Fourth United Nation's Conference on Women (FUNCW) was held in Beijing in 1995. It introduced a variety of foreign feminist thoughts to China, including ideas on domestic violence and sexual harassment (which later inspired movements).

A government-held discussion on women did successfully bring back the politicization of women's personal issues. The focus in this time was largely non-confrontational. It involved educating college students, government officials, and women in local communities, as well as policy lobbying. There were two different types of actors that emerged.

First, female cadres, intellectuals, and professionals established women's non-governmental organizations (NGOs). These NGOs did a lot of work, including hosting workshops, providing places for women to share their stories with each other, and pushing for legislative change. Most of these NGOs were cooperating with the ACWF.

Secondly, intellectuals and feminist scholars pushed for women's studies in universities. Gender and queer studies were also established to an extent. These courses were incredibly important for instilling feminism in college girls in the 2000s. They even encouraged underground LGBT groups in universities.

Digital Activism

Finally, starting in the early 2000s, digital activism emerged. Technically, its roots lie with the ACWF and some women's NGOs creating websites, but it really took off with the prominence of social media and "We Media" (Weibo and WeChat), which took off after 2010. The internet is incredibly beneficial in some ways. For one, it's helpful for grassroots activism because arguably, anyone can gain a platform and it's easy to connect like-minded people together. You can create your own online community or space to share. Anything you share publicly is very visible. There was also a lack of any governmental support or monetary resources, so the internet provided an easy way to bypass that and still contribute to change. Feminists in this time also benefited from the work of their predecessors. Many took the women's studies courses established in the 2000s. Veteran feminists from the 90s also hosted Gender Equality Camps starting in 2012 for these new, young feminists.

Still, using a digital platform has its downsides. As much as feminists can gain a following, so can misogynists. The term "extremist feminism" became a common criticism of digital feminism. It also doesn't necessary translate to any progress in the public sphere. It is much easier to talk about something on the internet than it is to destigmatize its discussion in public. There is also the push to sensationalize feminism to get views; it has to be dramatic and interesting to get anyone's attention. Additionally, China presents the unique challenge of dealing with state surveillance. The Great Firewall, amongst other systems in place and Chinese social media platforms themselves, regulate both foreign and domestic online content for Chinese netizens. Any popular terms being used to discuss feminism can be blocked. The term "feminism" itself is even censored. Therefore, modern feminists have to play the game, both sensationalizing their actions and dodging censorship.

A turning point in digital feminism was in 2015, when the government cracked down on feminist activism, both online and offline. The internet censoring system erased many online campaigns, and has continued to do so since then. Digital feminism had become very confrontational. Older generations of feminists labeled themselves 女性主义者nvxingzhuyizhe (activist for the culture movement on women and femininity). The new wave of feminists labeled themselves 女权主义者 nvquanzhuyizhe (fighter for women's rights), a political identity. The strategy became purposefully getting involved in heated online debates, putting the long neglected private issues women faced into the spotlight. After the crackdown in 2015, activism was hindered, but feminist Weibo and WeChat accounts became prominent as a means for women to share their stories and push for change. The international #MeToo movement and its Chinese adaptation #MituInChina both spread through Weibo and WeChat. The internet certainly provided a larger platform for this kind of "hashtag activism". Feminists could reach more people. Still, that comes with tradeoffs. The quality of the activism is diminished. These movements promote sensationalized stories from limited perspectives. #MituInChina was generalized to the case of a powerful, superior man versus the subordinate, powerless woman.

It's hard to say what the future of Chinese feminism looks like. However, I'd like to remain optimistic. In the digital age, feminists have shown great resilience, surviving the crackdown in 2015 and finding ways to adapt to censorship. With women's/gender/queer studies courses in universities, the youth are more and more aware and engaged with feminist thought. Ideally, feminists will persist and advocate for change politically and socially. Yet, it may be necessary to balance both online and offline activism in order to do so.

References

“Fourth World Conference on Women.” United Nations, United Nations, www.un.org/en/conferences/women/beijing1995.

Hou, Lixian. “Rewriting ‘the personal is political’: Young Women’s Digital Activism and new feminist politics in China.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, vol. 21, no. 3, 2020, pp. 337–355, https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2020.1796352.

“Iron Women, Foxy Ladies.” Chineseposters.Net, chineseposters.net/themes/women.

Jabbarov, Bahram. “Great Firewall of China and Battle of Protocols.” LinkedIn, 18 Aug. 2023, www.linkedin.com/pulse/great-firewall-china-battle-protocols-bahram-jabbarov.

Liao, Sara. “Unpopular feminism: Popular culture and gender politics in Digital China.” Communication and the Public, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1177/20570473241268066.

Luo, Xixi. “我要实名举报北航教授、长江学者陈小武性骚扰女学生.” 微博, 微博, 31 Dec. 2017, weibo.com/ttarticle/p/show?id=2309404191293831018113.

Yang, Chun, and Yongyuan Zhou. “Shifting the struggle inward: Mainstream debate on digital grassroots feminism in China.” Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, vol. 29, no. 1, 2023, pp. 69–96, https://doi.org/10.1080/12259276.2023.2183453.

Comments