Male Virtue (男德)

- Grace G.

- Apr 30

- 3 min read

Digital activism can transform offline movements into an online phenomenon or vice versa. It can also take advantage of internet buzzwords to comment on politics and gender inequality. In my mind, this is the sillier aspect of digital feminism. It uses parody to make a point. One example of this is the term 男德 nande, meaning male virtue (Hu and Wang 2025). Nande is intentionally the male version of the Confucianist term 女德 nvde, meaning female virtue. Of course, only the latter was actually enforced throughout China's history. The general idea of female virtue in Confucianism is the Three Obediences and Four Virtues. Women are expected to obey their father prior to marriage, their husband after marriage, and their sons once widowed. The four virtues are feminine conduct, feminine speech, feminine comportment, and feminine works. In essence, they are obligations for women that restrict them to traditional gender roles, subservient to men and the embodiment of femininity for their entire lives.

Nande was intentionally created by netizens to poke fun at the concept of nvde and strict gender roles by "imposing" the same kinds of expectations on men. It's largely used to criticize the behavior of Chinese men because they aren't being virtuous, though it is sometimes used to praise those deemed virtuous. The point is not to enforce the traditional roles for men, though. Instead, it reverses the male gaze to point out how ridiculous it is, playfully praising or accusing men depending on if they obey the rules of nande.

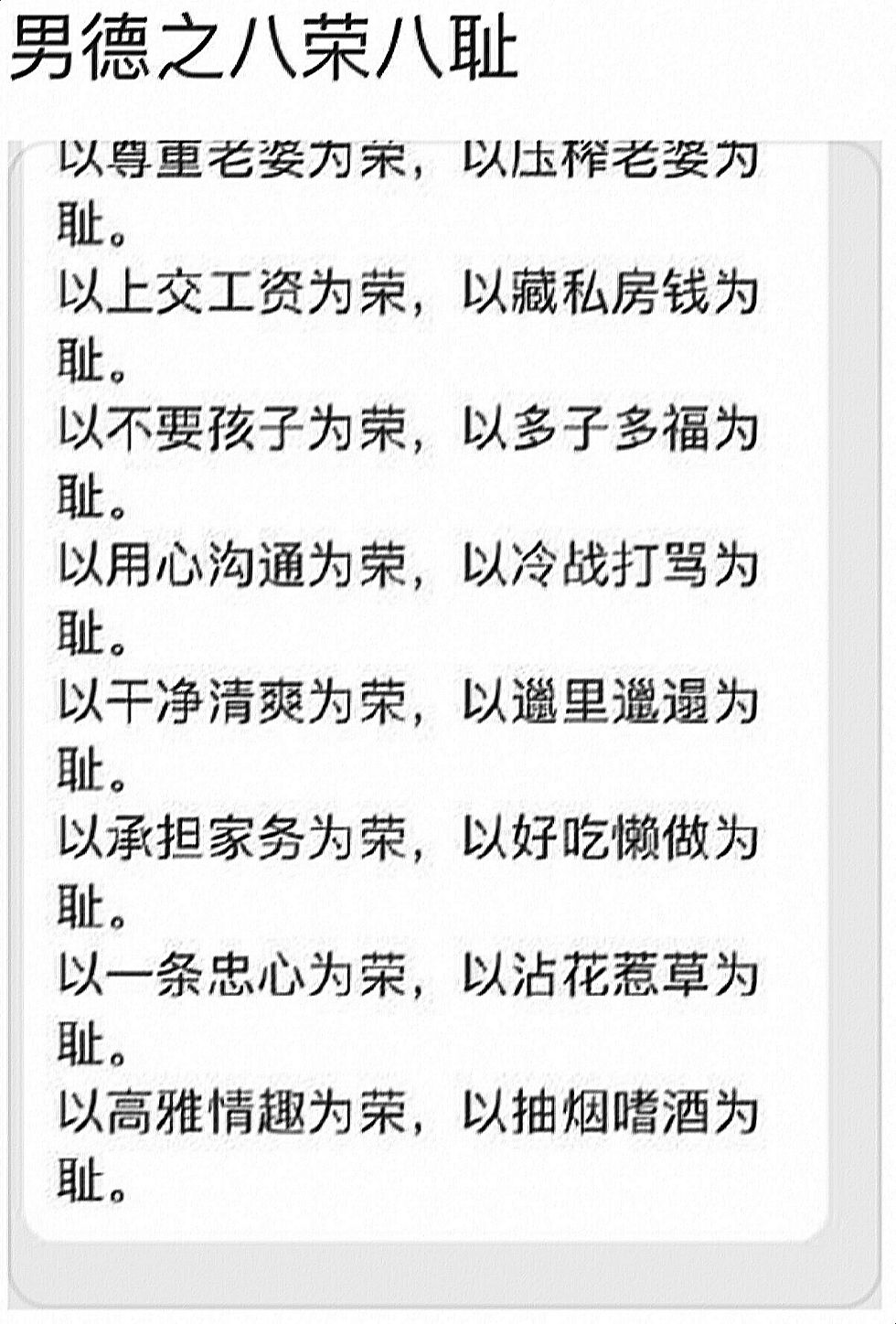

A specific Weibo post adapts the structure of the Socialist Maxims of Eight Honors and Eight Disgraces (社会主义八荣八耻) to list the eight honors and disgraces of nande. The principles align with socialist ideals. Connecting nande with official slogans resists the counterarguments misogynists often make, that feminism is a foreign concept and goes against social harmony.

Additionally, a study on the use of the term on the internet revealed that it's most often used in fandom culture to address young male idols referred to as 小鲜肉 xiao xianrou or little fresh meat. It's clearly representative of the female gaze, and even allows women to express their sexual desires online (which is important since women's sexuality has long been neglected by Chinese feminism).

Less serious forms of digital activism like this have potential for dodging censorship because they aren't directly confrontational or obvious. This does come with the concession that the movement isn't as strong, though. However, I think it still holds merit as a unique method that plays on the fun parts of social media, and it's creative. These Weibo posts sound much more like Twitter than the ones from the #MituInChina movement. It may not be as effective with older generations, but I hope that internet buzzwords like nande become an effective way to connect feminists with each other and point out the flaws of the patriarchal system in a more digestible format.

References

Hu, Yuqi, and Yunhong Wang. “The rise of nande : A case study of digital feminism in

China.” Feminist Media Studies, 2025, pp. 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2025.2468417.

Comments